This is also Cross-Posted on Medium if you want to comment there.

A few weeks ago a company approached me if I’d be available to give a series of talks and Q&A for senior developers. Their question was how to deal with the problem that there seems to be an upper limit to technical careers. At one time in our career we have a decision to make if we want to keep being technical or moving into management. It sounds odd, but there is a lot of truth to it.

A gap in company hierarchies

Throughout my career I found that there is a limited amount of levels you can climb as a technical person. This sounds unfair, especially in companies that pride themselves on being technical. The earlier you are in your career, the more annoying this seems.

When we start, we love being developers. We see technology solve problems in a logical and enjoyable fashion. Much less icky, slow and error-prone as human communication. It makes us believe that you can solve everything with technology. Which is great, as this is also what excites us. People excited about their jobs work better.

On the whole we earn good money, have a high-quality work environment and feel we could do this forever. Sometimes we get too excited about developing. We don’t realise that we burn out or are being taken advantage of. I’ve seen product managers trying to make a mark by releasing a product before the deadline. They then coerce junior developers to work too much or cut corners. At the cost of endangering the quality and even the security of the product. And the mental health of the developer.

Seeing this dedication it feels weird not to have technical role models to look up to. At a certain level in the company it seems you need to stop coding and do things we don’t like to do instead.

What annoys us?

We love to complain about things at work. As developers we are quick to blame things beyond our control for failures. It can’t be the problem of the technology or our skill, right? We’re excited about what we do, and that means only good things can come out of that.

Often we see products go wrong. Most of the time because of business decisions that make no sense to us. Business decisions that interfere with our development plans. People get allocated elsewhere, budgets of exciting products get cut. Products we’d love to see go live as their technology is cool and innovative.

Meetings are plentiful, not productive and get us out of our development zone. Why should I sit in a room talk about what I do when the version control comments do the same job?

Time and allocation estimations keep being wrong. Either we’re allocated to a project that doesn’t need us, or we don’t have enough people. We run out of time when developing products and often by the time we release, the market stopped caring. Or our competitor was faster.

Whilst underestimating it ourselves, we often see other engineers burn out. There is a huge churn of people and it is tough to build teams when people keep leaving and new ones get hired. It is hard to keep up good quality in a product when the team keeps changing. It is tough to innovate when you spend a lot of time showing people the ropes. And innovation is something our market seems to be running on. It is also what excites us as developers, We want to do new, cool, things and talk about them.

We face the issue that we keep having new people but there is never enough time for training. When we read the technology news feeds there seems to be so much to look at but it is beyond our reach. Instead we spend our time re-educating joiners on how things work in our company. And it feels that we ourselves fall behind whilst our job is to be inspiring to junior developers.

What are we worried about?

As developers in the trenches and in the flow of excitement we worry about a lot of things. We find that keeping up with technologies is a full-time job. If you’re not on the bleeding edge you will only get boring work or someone will take your job. This is odd considering the amount of job offers we get and how starved for talent our market is. But we worry and we stress out about it. Younger, fresher people seem to be much quicker in grasping and using new tech as we are.

We also see coding as a fun thing and we don’t want to stop doing it. We remember that we had no respect for people who didn’t write code but use products instead. We don’t want to be those people, but it seems that to advance our careers, we need to.

Turning the tables

It is a good thing that these thing annoy us as they are an opportunity for us to turn the tables. By shifting into a role that is a technical hybrid you can battle some of these annoyances. The hierarchy gap is an indicator that there is a rift between the technical staff and management. A gap that is costly and hinders our companies from innovating and being a place where people want to work.

It is painful to see how clumsy companies are in trying to keep their techies happy. We do team building exercises, we offer share options. We pay free lunches and try to do everything to keep people in the office. We print team T-shirts and stickers and pretend that the company is a big, happy family. We pay our technical staff a lot and wonder why people are grumpy and leave.

All these things are costly and don’t have the impact our companies hope for. The reason is that they lack respect and understanding. When the basic needs of humans are met there is no point adding more creature comforts. There is no point earning more money when you have even less time outside work to enjoy it.

What gets us going is a feeling of recognition and respect. And only peers who’ve been in the same place can give that. There is no way to give a sincere compliment when you can’t even understand what the person does.

And this is where we have our sweet spot. Our companies struggle for relevance in comparison to others as much as we do with out peers. And often they lack input from us. Instead of implementing what has always been done a certain way we can bring a reality check. The market keeps changing and it is up to us to remind our companies what excites technical talent.

There may be a path already available to you – or you have to invent one to do that. In any case, your first job is to become visible to your company as someone who cares and wants things to change. This means partnering with HR, hiring and PR. It also means selling yourself to management as someone ready to change things around.

Becoming a fixer of bigger problems…

The fun thing to remember is that as a company in the technology space, everybody has similar worries. Think you are worried about falling behind? Your company is much more worried, and you are closer to the subject than the people running it.

Research what worries you, share how you keep up to date and what it means for your company. It makes sense for a company to get the gist of a new technology from someone who can verify it. A lot more sense than falling for a hype and buy a third party product or consulting on the subject.

Often we’re asked to implement something hot and cool that doesn’t make any sense. The reason was most likely some PowerPoint circulating in upper management. A presentation based on what excites the tech press and not what makes your product better. Try to be there with advice creating that PowerPoint before you have to deal with its impact.

Retention of talent is another thing every company worries about. Churn and burnout of engineers is a big issue. Try to offer solutions – things that help you and keep you here. Every engineer coming through the door is a 20,000 GBP investment. Even before they wrote their first line of code or got access to the repository. Every engineer staying at your company is a worth-while investment. Making sure you help find your company ways to keep people is a big plus for you.

Another way to shine is by bringing in new talent. It is a competitive market out there and it is hard for a company to find new engineers. As developers we’ve grown weary of terrible job offers. It is not uncommon to see demands like five year experience for a one year old technology. You can help prevent your company from such embarrassment. Work with your hiring department to draft sensible job descriptions. Even better, go to events and meetups. Look through pull requests and comments on repos to spot possible candidates.

Find ways to encourage your engineers to hire by word-of-mouth. This is is how I found my last five jobs and this is also how I made up for some income gaps. A company that pays a bonus for each hired person has employees as advocates. People we trust are more likely to be good colleagues. Better than random people you have to filter out with a good interview process. Try to make your company visible where developers are by being a great example, and you may stir interest.

Nonsensical job offers are a symptom of a general problem with internal communication. This is rampant in our market. Developers hate managers, managers don’t get developers. You can mediate. It is a tight-rope walk at times as you don’t want to come across as someone trying to please management. But it is a necessary step, and if better communication is the result, worth your time and some arguments.

External communication and marketing is another department you can help with. How often did you facepalm reading advertising by your company? Help avoiding this in the future by being a technical advisor.

Overall, this is about being an ear on the ground for your company. To non-technical people in a company navel-gazing is common. The job of marketing is to make your company’s products look good. Often this means that people get a bit too excited about your own produce. They don’t compare, they don’t even have time to look at what others are doing. This is a good chance for you to keep up with what the competition is doing and tell what it means to your company. You’ve done the research for them, and that is worth a lot.

New skills that are old skills…

The fun part about being a coder is that you don’t have to deal with people. This ends when you want to move further up. Your “soft skills” are what will allow you to stay technical and have a new role. Your technical skill is an asset, but it is also limited – even when you don’t want to admit it yet. Being a technically skilled person with good communication skills is the sweet spot to aim for. The higher you communicate upward, the less people are interested in technical details. Instead they want to see results, impact and costs.

Sales people know that. Learn from how they work, but stay true to what you talk about. Instead of selling by hushing up bad aspects, sell your technical skill to prevent mistakes. Instead of bad-mouthing your companies’ competitors, be in the know about them and show your company what to look out for. We all sell something. Why not sell what excites you and your experience instead of having to patch what others messed up?

Flexibility is the key

My career took off when I stopped caring where and when I worked. Being open to travel is important. Most communication problems in companies are based on time difference. Be the one that is available when others are. Try to be open to any technology and listen to their benefits and problems. You will not live and die in one stack.

Things not to worry about…

You are not betraying the brotherhood of coders by moving up. They have no wrath worth worrying about. You will be asked constantly if you still code. But it is natural that you will lose interest in being on the bleeding edge all the time and doing the work. We all slow down and want a life besides chasing the cool. You will also wonder why the hell everything is so complex now when it used to be so simple. Even when you don’t code all the time, you won’t be bored. Consider this a chance to fix what always annoyed you.

You will be praised for things you haven’t done. Much like you are praised as a developer for things you don’t consider good. People can’t measure what is good, they see what you do and are impressed. Take the praise but make sure to share it with those who did the work.

Realities to prepare for…

Let’s re-visit the worries we have as developers and give them a reality check.

Keeping up with technologies is a full-time job. It is! So find a way to convince your company and managers that you are good at doing that. Remember that you need to free up a lot of time on your schedule to do that. This means not doing all the work but getting better at delegating. It also means giving more conservative estimates about your deliveries and deadlines. This can be tough to do. Especially when you made the mistake of establishing yourself as the person who can get things done – no matter what.

You can only understand a technology when you use it. True. But you will never have enough time to do that. Triage the evaluation and using of technology to your team. This is a great way to empower people and allow them to work on their communication skills. It is also a good way to keep your team interested. Allowing a developer to stop ploughing through a bug list and evaluate something new and shiny instead feels good. If you rotate these assignments you don’t cause jealousy or show favoritism. You don’t want your team to feel bored or underappreciated whilst others do cool stuff. So let them do cool stuff and keep buffers in your allocation planning that allows for it.

Younger, fresher people seem to be much quicker in taking on new tech as we are. True. So allow them to do that and be a good leader for them. You will get slower the older you get. You will be hindered by real life demands. The more experienced you are, the more likely you are to discard new things and stick to what you know. Let others inspire you. You might not be up to going all-in with some experimental technology. A younger person reporting to you can be and you can learn something by guiding them.

Coding is fun. We don’t want to stop doing that. True. You should never stop coding. But isn’t it time you earned the right to code what and when you want to? Things you know well are a great opportunity for a junior developer to learn. Don’t take that away from them. We shouldn’t be bored by our code. This leads to stagnation and is the antithesis of innovation.

We remember that we had no respect for people who didn’t write code but use products instead. I sincerely hope you grew up. Software Development is a service. We build things to empower people to achieve goals. The more complex these systems are, the more we move away from coding. There is no medal for being hard-core. First to market is a thing.

Other realities you have to face are things you may not be familiar with or you are in denial about. These things happen though – all the time.

There will be a time when you are too senior to be assigned work. You might as well take action on that. Make sure that you have junior engineers you trust to do that work and be the firewall for them. When you are too senior to do a job, make sure you help the product owners find the right people in your team. Your job is to take the demands from top down and translate them to manageable chunks for your team.

Anything you do can get canned at the last moment for reasons beyond your control. Take it in stride and learn from the mistakes you made. Be stringent in noting down what went wrong. That way you don’t repeat the mistakes.

You are diving into the deep end of corporate politics. Who you know, and who you impress is often more important than what you know. Networking internally is a big thing. Concentrate on corporate levels, not on individuals. People leave.

Things to start with…

I hope you found some things that resonated with you here. There are many ways to get into a place where you can stay technical and move up in your company hierarchy. Most are fresh though and companies need to change age-old approaches to the topic. It is exciting to be part of that change though.

A few things that helped me get to this place are kind of obvious:

Consider contributing to open source. Either by participating in projects or open sourcing your own products. Open source is by default a communication channel. It helps you find talent as people join your company knowing your product. It helps your company become more visible to developers. And it gives your team a sense of achievement. Even when some internal product goes pear-shaped, there is something out there. Even when people leave the company, they have something to take with them. Contribution to open source is portable. You can show the outside world your skills – no matter who pays your wage.

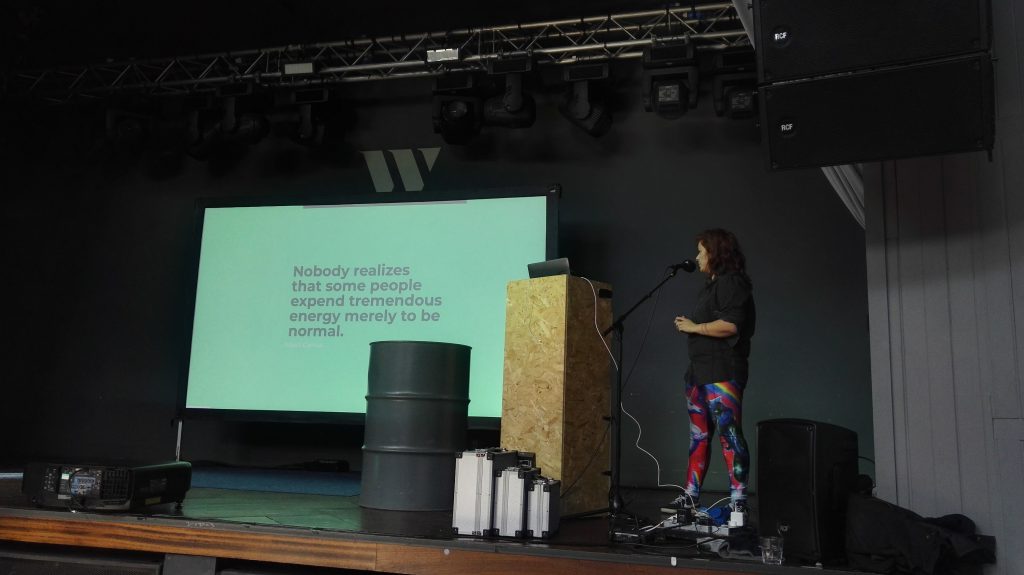

Look for events and meetups to attend. Instead of taking your team to the bowling alley or an escape room to do team bonding, why not attend an event? You learn something, you can talk to people about your work and you get out together. Many events also offer jam sessions or B-Track events which are a great opportunity to submit a talk. Of course, you can also host a meetup or guest presenters at your office.

Foster an internal culture of communication. When you get people to attend events on company time, ask for them to present about the event in the office later. This helps with a few things. It means you know they went there and paid attention. It means others who couldn’t go get the information. And it means your team already gets used to presenting to a group which is important later in meetings. Often technical people know solutions, but don’t speak up in meetings as they don’t see the point. The more we get used to it, the more we embrace the idea that our points only get rewarded when we tell people about them. There are many ways to foster communication and some are a lot of fun to do. Like lightning talks about solved issues in products or even something as silly as Powerpoint Karaoke.

Aim beyond the finish line

The main thing to remember as a senior developer struggling with having no role to aim for is to aim beyond that role. Your company invested a lot in you and relies on your judgement when it comes to technical delivery. It also relies on you to lead a team and keep them happy. You also deserve to be happy and to make that happen you can’t keep things as they are.

One of the biggest mistakes we make as technical people is to make ourselves irreplaceable. We put a lot of effort into our technical products and it is hard to let go. Often we stay in a position even after all the joy went out of it and we don’t believe in the company any longer. Because we want to finish that project and see it go out of the door.

The seemingly sad fact of the matter is that nobody is irreplaceable. And that project the company keep stalling on isn’t going anywhere. And if you left to pursue other things not everything will go to pot, either. The main step to get ahead in your career is to understand that. You are replaceable and you have to take an active role in it. Hire people that are technically better and more interested in new tech than you are. Don’t be afraid of them moving into your role. Instead support them and find worthy replacements. Change in companies is a given, you can be part of those driving it or worry about how it will affect you. I’ve always rolled with the punches and it served me well. Hopefully you can do the same.