I just found an old CD with a projects folder of work I did in 1998 – 1999 as a web developer and I am in awe about a few things.

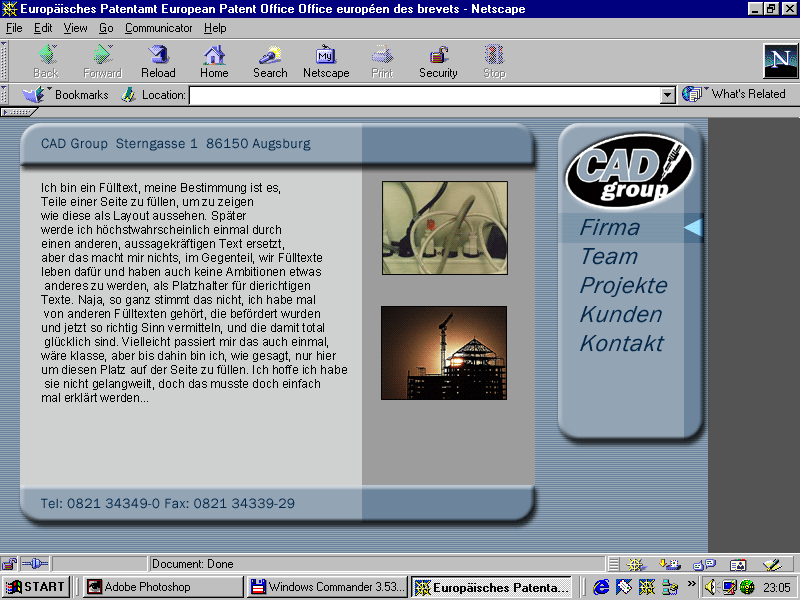

Well, first of all, let’s get out of the way how I – successfully – advertised my business:

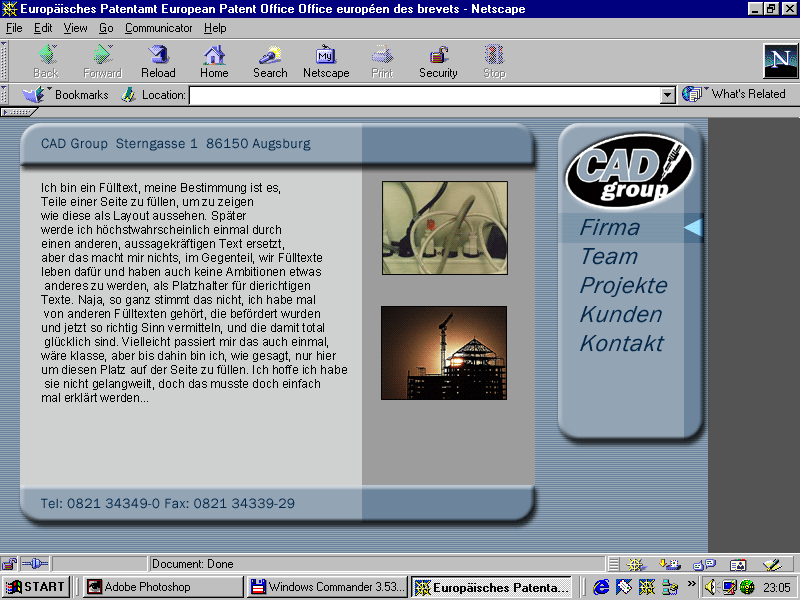

Then I discovered a full size screenshot of how I worked using Netscape 4 (I was an avid Internet Explorer avoider back then):

There are a few things there:

- Browsers had a lot more interface back then than they have now

- There were no tabs – each page was a window

- Netscape was a suite of tools (much like Firefox seems to become now), if you look bottom right, there is the browser, email client, chat client, address book, and Netscape Composer, a WYSIWYG editor

- This was the full resolution, 800 by 600 was all there was for me

- You notice that there is no editor open, the reason was that when I had Photoshop open, my machine wasn’t fast enough to run more. The Editor I used was either Notepad, or later Homesite

- Windows Commander was my replacement for Explorer as it allowed full keyboard interaction (F5 to copy, F6 to move, F7 to edit…) and it also was an FTP client. I still use it from time to time, it is now called Total Commander and I use it on Windows and Android.

- There was some sort of Virus scanner in use – no idea what icon that is

- This was Dial-Up as indicated by the two linked computers next to the speaker icon

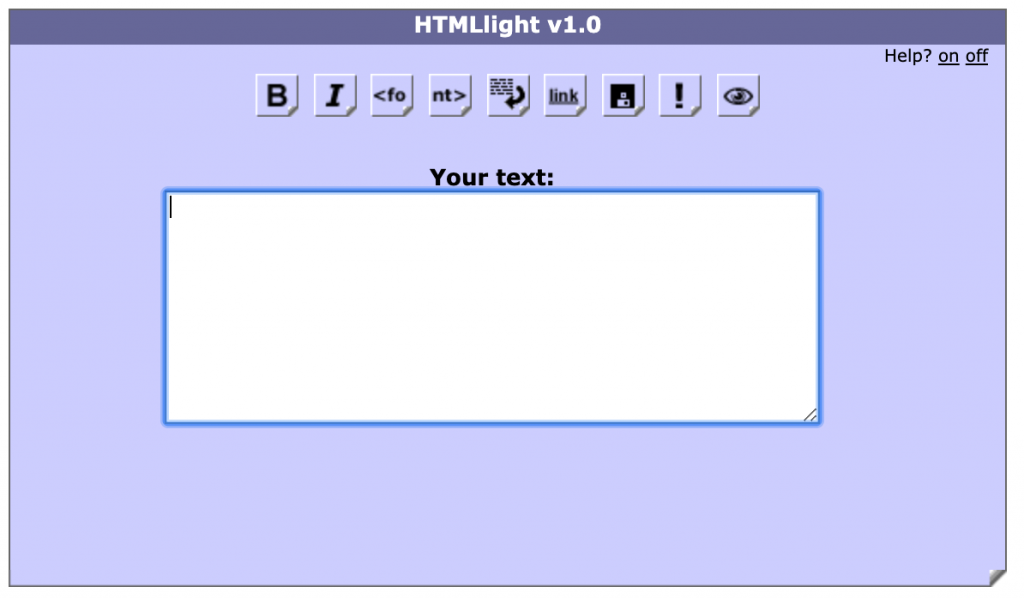

OMG, I wrote an HTML editor!

One thing I found in the folder with this screenshot was an in-browser HTML editor I wrote for a company to create their intranet pages / newsletter with. This one was written in DHTML (Dynamic HTML, a nonsense term describing JavaScript interacting with HTML) and it supported IE, Netscape and Opera.

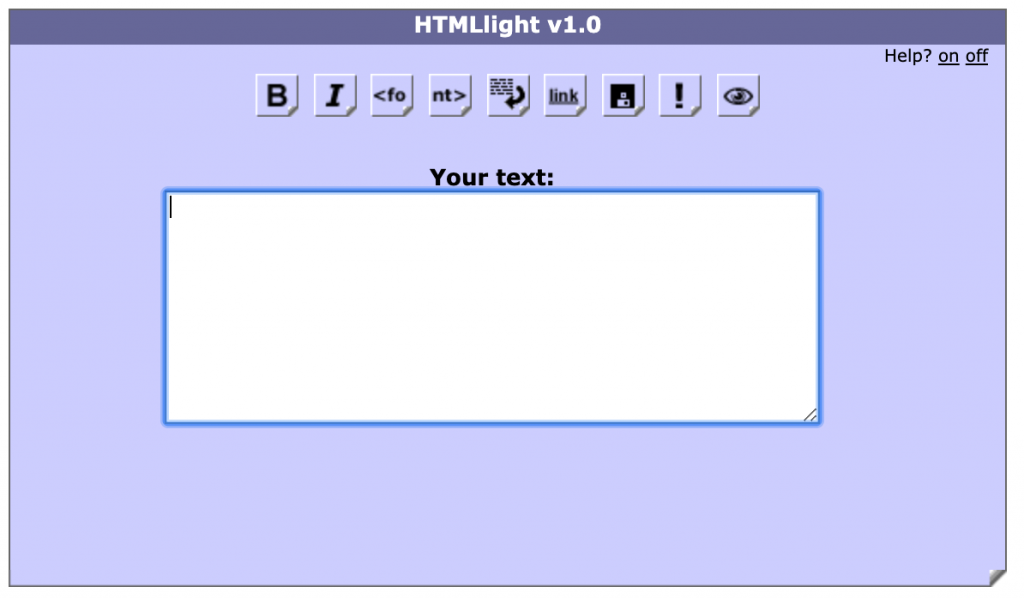

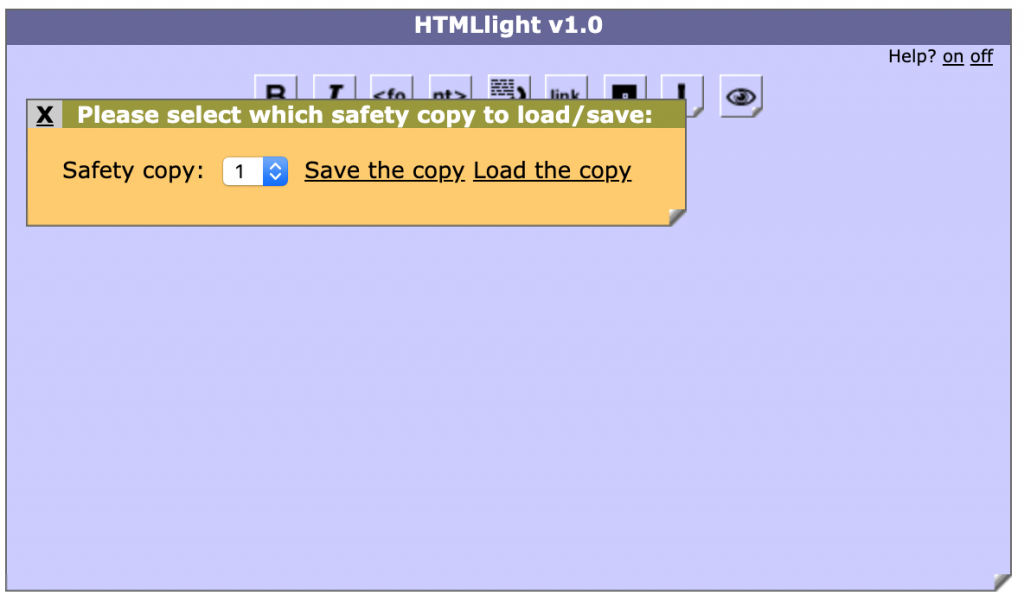

This is what it looked like:

Basically a text box with some buttons to add B, I, FONT, BR, A elements to text. There was also a storage button to save up to 6 texts, an undo button and a preview. All of this came with interactive help you can turn on and learn about the buttons.

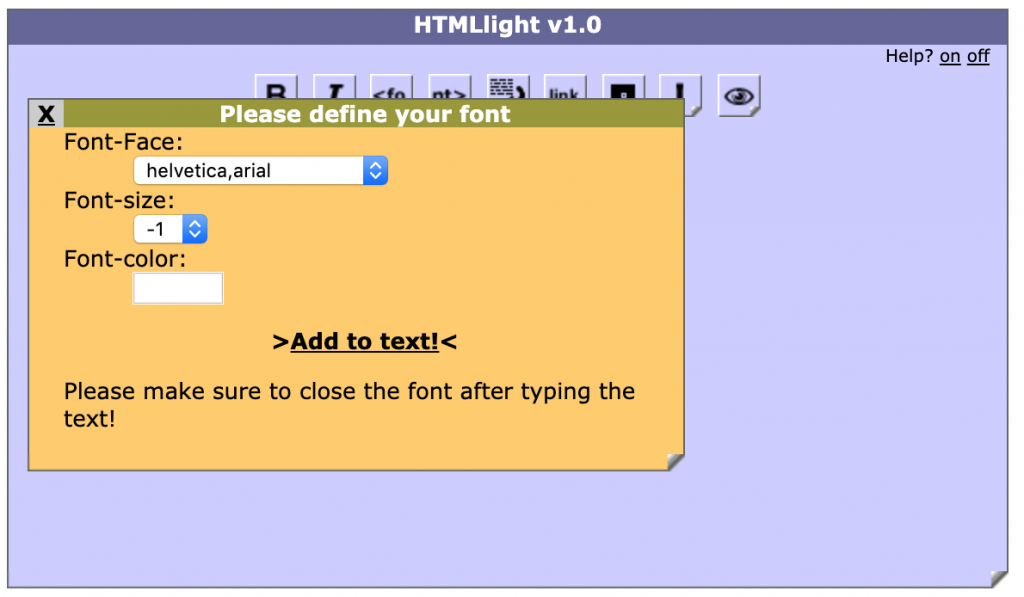

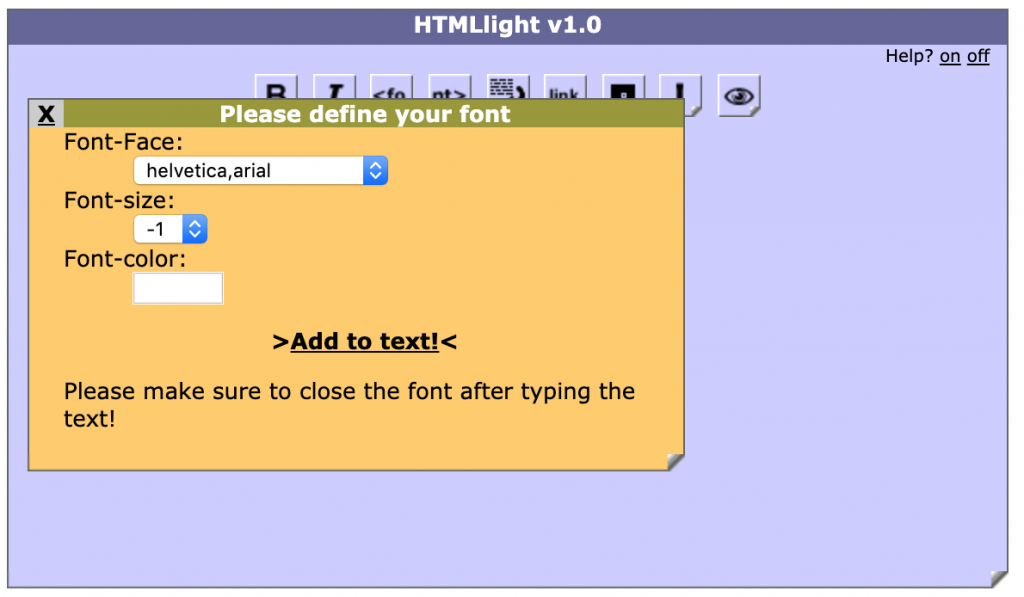

The font picker came with a preset list of safe to use font faces.

The storage interface was the most brazen – in essence, all I did was put the text in hidden form elements :).

Now, the fun bit is that the interface still works in modern browsers. I put the code up on GitHub and you can see it in action here. Well, almost, as I made a mistake in the JavaScript to add the results back to the main text field nothing gets added. However, a simple fix made sure that it now also works in modern browsers.

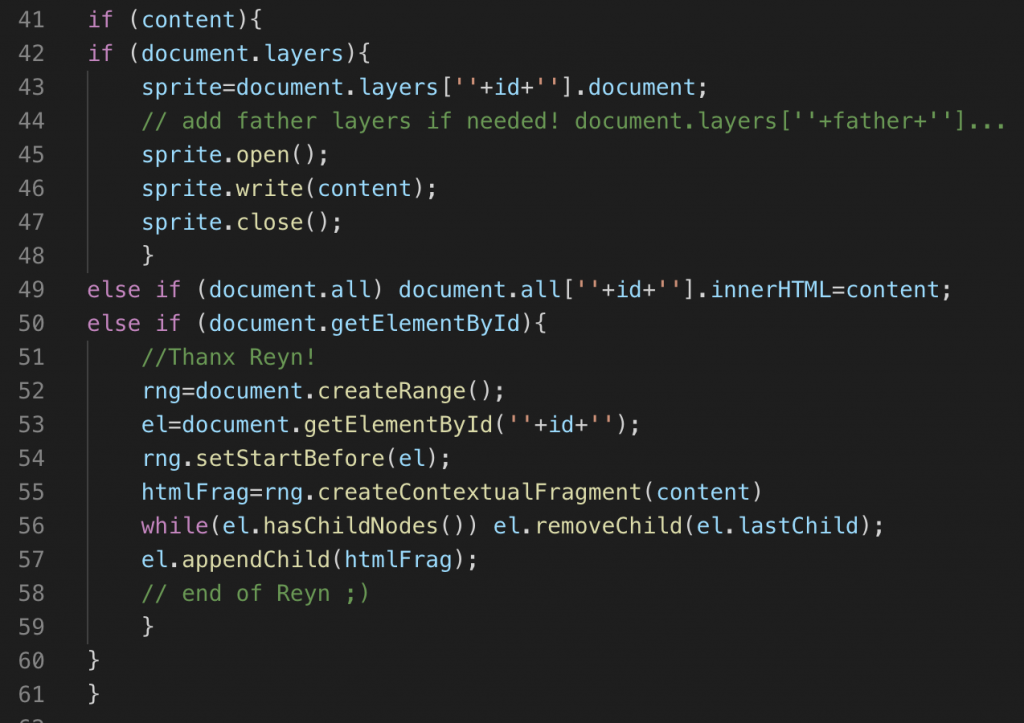

The code (the horror, the horror)

Let’s take a peek at the horrors I had to do to make this work across different browsers.

Let’s start with the HTML:

- The layout is achieved with HTML layout tables using a spacer gif to ensure that the tables get the right size and not more. Notice you had to repeat the width of each cell in the width attribute of the TD and the width of the spacer image in it.

- Each table cell needed its own FONT element to define the font – this didn’t come down from the body element. This is one of those amazing things that CSS gave us we don’t celebrate enough. The cascade was a life saver when it came out.

The CSS:

- CSS was already a thing, but rudimentary and not well supported

- In this project, I only used it to absolutely position all the help “windows” of the UI. This was a clever trick, as there was a weird – I guess – bug in Netscape that made every absolutely positioned element behave like a LAYER element without having to write one. Earlier Netscape needed you to use LAYER elements which didn’t work in other browsers, so we needed to repeat them for IE and for Netscape.

- Interestingly enough I used clip here to ensure that the “windows” don’t get bigger with content, something that kind of has a revival in the CSS world.

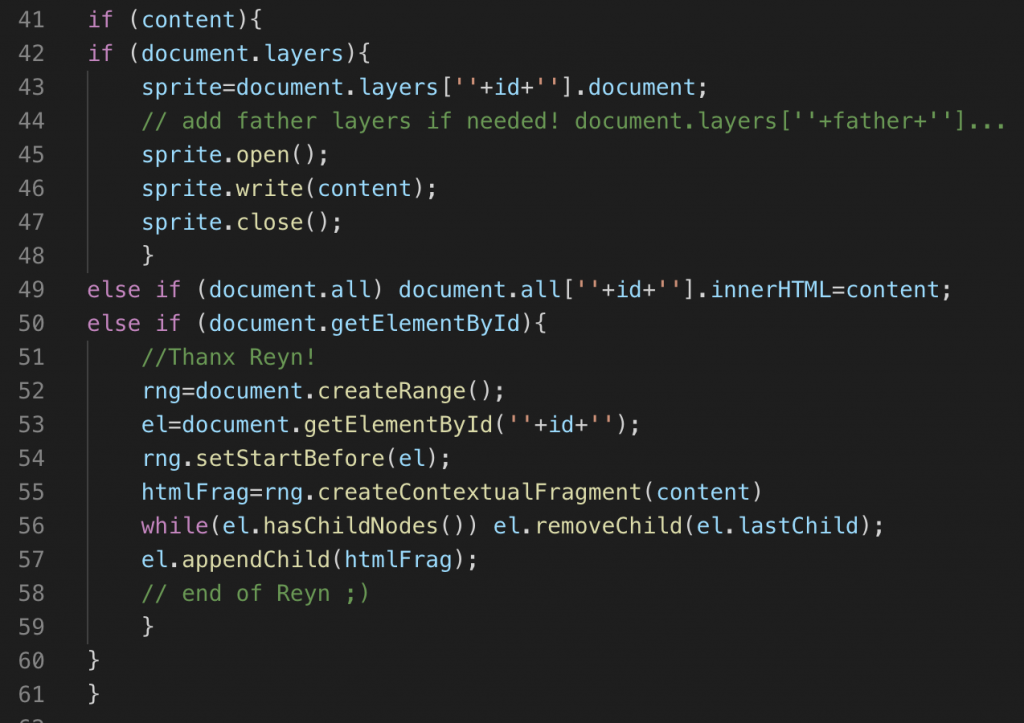

The JavaScript:

Where do I begin? As event handling was a pain across browsers (with IE having a different model) I used links with the javascript: pseudo protocol to execute functionality. This was a necessary step, but probably is the reason why this horrible mixing of HTML an JavaScript functionality still is a thing with developers now. Basically this was a Frankenstein monster of code that was done to work, not to look pretty. I later on understood the folly of my ways and wrote the Unobtrusive JavaScript course explaining how to use newfangled things like event handling :).

- It seems I didn’t give a hoot about scoping. All JavaScript variables are global and I didn’t even use the var keyword

- There is a lot of repetition there, I liked to copy and paste and change a few things instead (admit it, that’s what people do on Stack Overflow now)

- The reusable domlay() function was a long job in the making and one of my crowd pleasers in any company I worked for. It allows you to place an element on the screen, show and hide it and dynamically change its content. Notice the convoluted part of changing the content in a DOM-1 getElementById world – luckily later we got insertBefore(), replaceChild() and subsequently innerHTML. Internet Explorer’s document.all already had innerHTML, but it felt dirty.

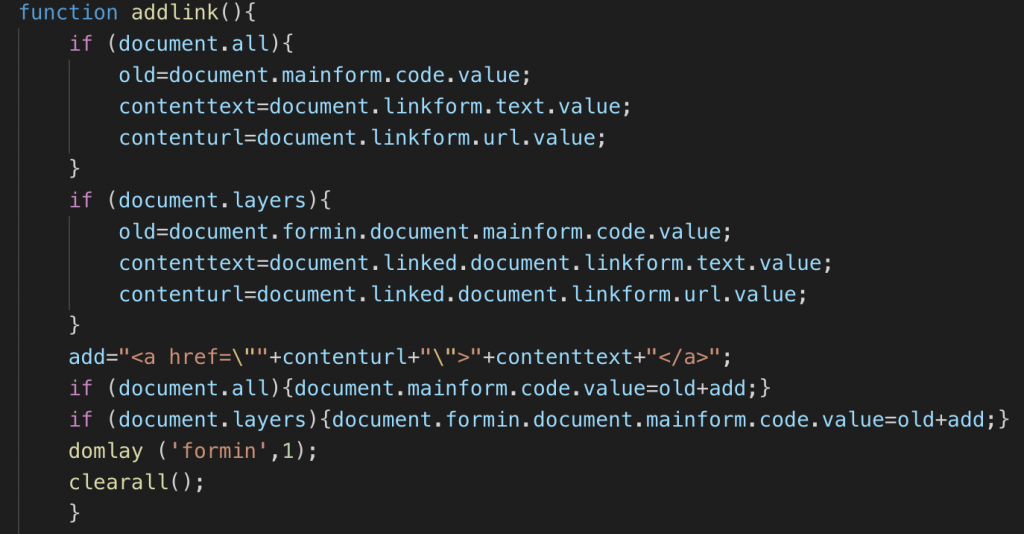

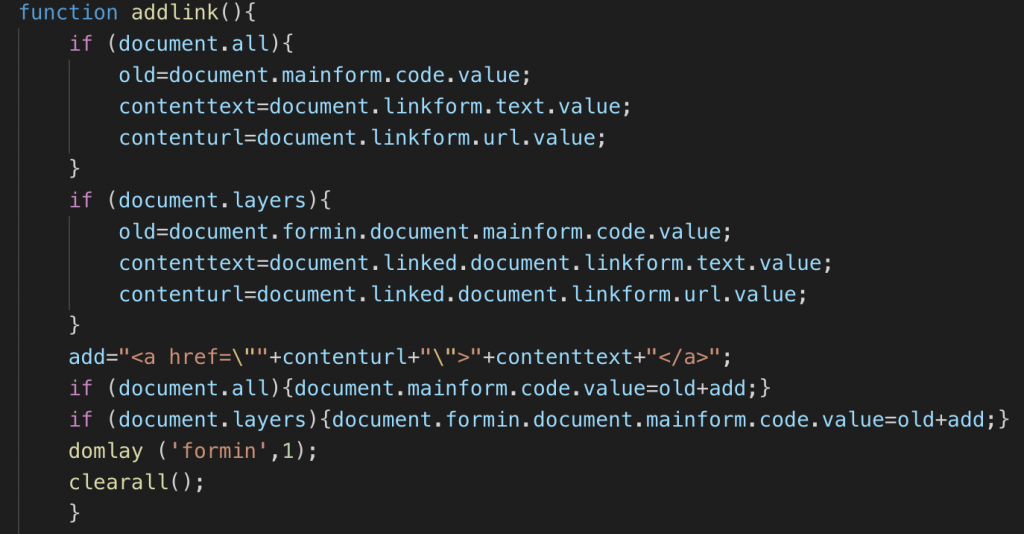

- Netscape treated each LAYER as an own document. This is why you needed to access the document inside the main document. This made accessing a form inside a layer to read the value and to access it to write quite long to write as the addlink() function shows:

- An interesting thing to see is to get the value of a SELECT form element back then wasn’t as easy as it is now. These days you can get a reference to the element and read its value. Back then you had to get its selectedIndex property and read out the element of the collection of options inside the select. Looking at the mess that is addfont() shows that we did some clever fixes to the DOM API over the years.

- Overall this code is sloppy as hell when you look at it now, I have truthy/falsy checks with == and != instead of triple checks and my if statements only check for document.all or document.layers instead of also supporting document.getElementsByTagName. This is understandable, as it wasn’t done yet and no browser supported it. Netscape 6 was the first to do so, and it kept crashing. I now fixed this to work with newer browsers by simply appending a if (document.all || document.getElementById) to the read/write functionality.

I feel happy about our stack now, do you?

All in all I am happy to have witnessed these days but I also don’t miss them at all. Seeing how far browsers, the standards and especially tooling has come since then is great to see and I am happy to be part of this process.

Next time I am tempted to complain how broken everything is, I’ll look back and shut up :)