One step ahead and two steps back: are apps really the future?

Tuesday, January 15th, 2013My esteemed colleague Luke Crouch put together an interesting piece entitled Packaged HTML5 Apps – are we emulating failure which resonates quite well with me. In it he describes the process of scanning a QR code on a phone to check into a restaurant with Facebook. This right now involves installing a QR code reader, the Facebook app and many in-between steps that can not be in the best interest of the restaurant owner and requires a lot of patience from the user.

My reservations towards QR codes aside (hey, with NFC, this would be “tap your phone here to check in” – you hear that, Apple?) I think Luke points to a much bigger topic here that very much annoys me: we are stalling, if not moving backwards in the evolution of content delivery.

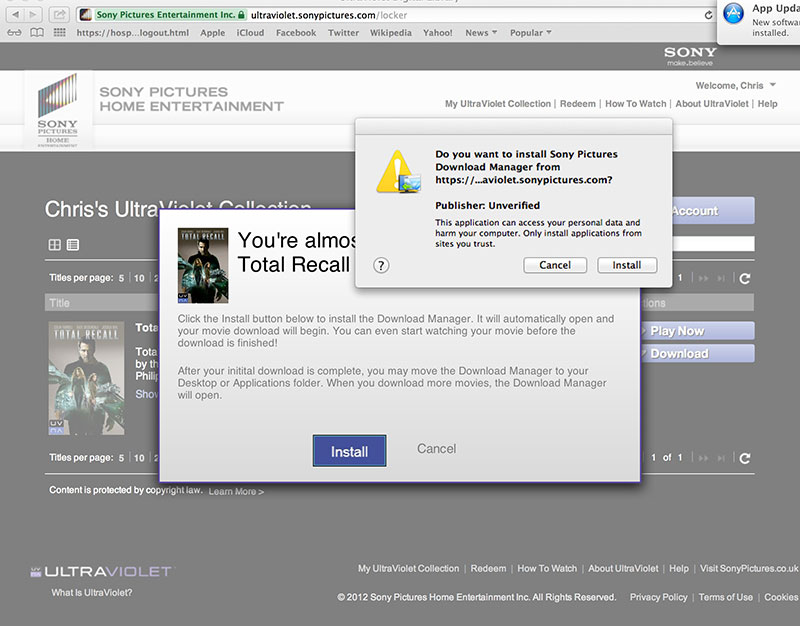

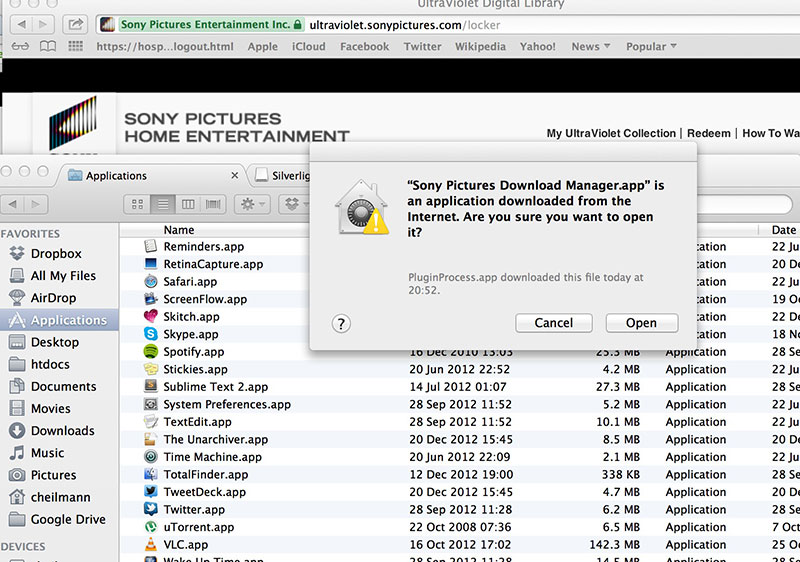

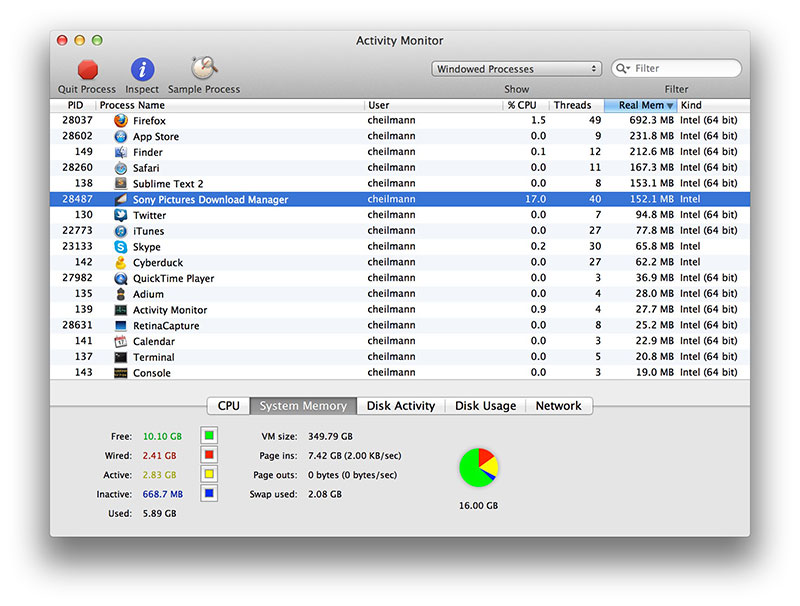

Let’s reduce the use case to the bare minimum here: an end user wants to get some content. This could be music, video, photos, a book, a map with instructions or a game to play. It all is data, zeroes and ones that if arranged in the right format make up the thing I want. Our job as the data providers should be not to throw as many barriers in the way of the consumer to reach that – our job should be to make this dead easy.

Whenever people say that “users want apps” then what they really say is “people want a thing that uses their hardware to the best of its abilities and be able to find that in a simple way”. Doesn’t roll as well of the tongue and sucks as a rallying cry, but describes the thing much better. I remember the days before the Internet, when software came on floppy disks in the mail and had to be installed and the third install disk had a read/write error so you had to call the company or go back to the shop to get a replacement. I also remember having to install a tool to cut up images for table layouts or to plan a route for my holidays. I also remember buying games and being told my computer is not good enough – always the sound card, which wasn’t as “Soundblaster compatible” as it pretended to be.

This seems ridiculous now and we laugh at the idea of not being able to just type, “Hackney, London” into the search box of our phone or browser and get a map back. Yet this is exactly the world we seem to crave to go back to when we say that apps are a much better experience and the future of our jobs and what people want.

What we do by praising apps and their simplicity is reward companies for locking users out – demanding the real Soundblasters so to say. We claim that app stores are easier for recovery and yet these companies pay a lot of money to advertise their apps and games on TV, in newspapers and in banner ads on the web. App stores are not easier. They do not scale. I wait for the day – which will come very soon indeed – where you can buy better placement in app stores, much like you could in “price comparison web sites” and search results.

If you took the app store model and compare it with something that happened to the web then app stores are the Yahoo directory which got killed by search with Google being the big innovator. We realised that it is far too much work to curate and edit a list of web resources when the format of them would allow publishers to promote their content and make the amount of people clicking it determine what gets shown first.

If you care to remember, we already had a failed attempt at app stores. Tucows, Download.com, Freshmeat.net and others tried the same for Desktop apps and nobody cares about them right now any longer and they fall into disarray and become a spammer’s heaven.

The focus on apps right now and the repeated myth that they are a much better experience for end users than the web are based on man-made barriers for the web:

- Apps have much more access to the device’s hardware

- App stores are promoted with the sale of the hardware

For everyone proclaiming that app stores are the better way to distribute apps I propose to check out the hundreds of empty app stores mobile service providers set up or the ones of hardware that is less successful than Android or iPhone. Wastelands full of frivolous apps and overpriced quickly converted and packaged old titles that were a success on other platforms.

This is not about what users want – this is about what the industry and distributors are used to and don’t want to change. A packaged app can be much easier priced and its distribution planned and tracked than a web app. Much like physical CDs and DVDs and books still have quite some time to vanish, the packaged app to me is the last of the dinosaurs when physical distribution was all you could do.

A lot needs to change till we realise that we have a wonderful way to distribute media called the Internet. Media that can stay fresh, can get updated when we need and discarded when we don’t want it any longer without having to download lots and lots of data each time.

Most of it is based on business models that are not flexible and see full control over the distribution as the only means of making money. Some of it is psychological. A neatly packaged app you need to install and uninstall seems like something more solid than a web app. It seems more trustworthy, whilst it also can cause much more damage. It is the “20% more” on a fizzy drink can you never knew you missed so much.

I am very afraid that if we do not stand our ground now and point out that apps are a distribution model of the past and not the future we’ll repeat the same mistake we did with Application directories in the past. Of course you can now list 23123 reasons why apps are better than web apps on mobile devices, but I dare you to find one that is not based on the device or OS vendor blocking access to functionality for non-native code. We praise a model of distribution for its simplicity based on lockout.

The argument you hear about this is that end users don’t care, they just want their apps. The fact here is that they don’t get told about alternatives. Again it is all marketing – damn good marketing, admittedly – but many demands from our end users come from seeing something and wanting it rather than needing it in the first place.