After 20 years of using Twitter, I just lost access to my X account. The reason is that I fell for a phishing attack. As someone who helps a lot of people with their security issues, this is embarassing, but I want to make it a learning experience, so I will share my mistakes with you so you can avoid them.

First Mistake: doing any security things in a rush.

It was the end of the week, I sent out a few last social media updates and already contacted my partner that I will soon be home and we go to drive to our weekend place. So I felt obligated to wrap things up quickly. I wanted to pick up my company iPhone and it had run out of juice. So I rebooted it and it asked for a Sim Pin which of course I don’t know by heart. It also asked for my iCloud password which I forgot as I just updated my computers to the latest MacOS. So I was in the middle of the reset-your-password dance with verification across different devices when the phishing mail came in.

Things I should have done instead:

- I should have just ignored the mail and finish my other tasks so I have full attention on the mail and not be in a rush.

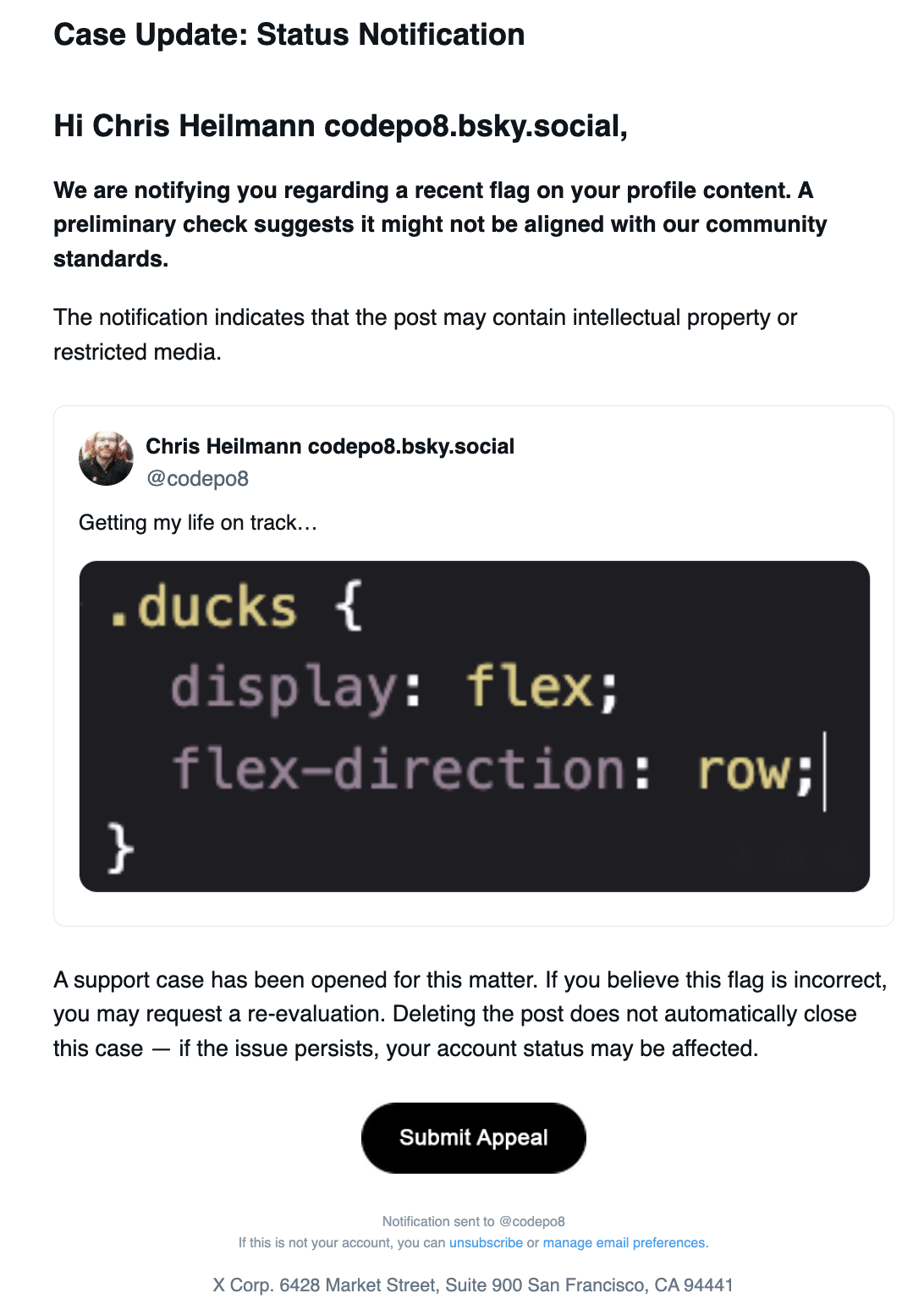

Second Mistake: falling for a pretty good phishing mail.

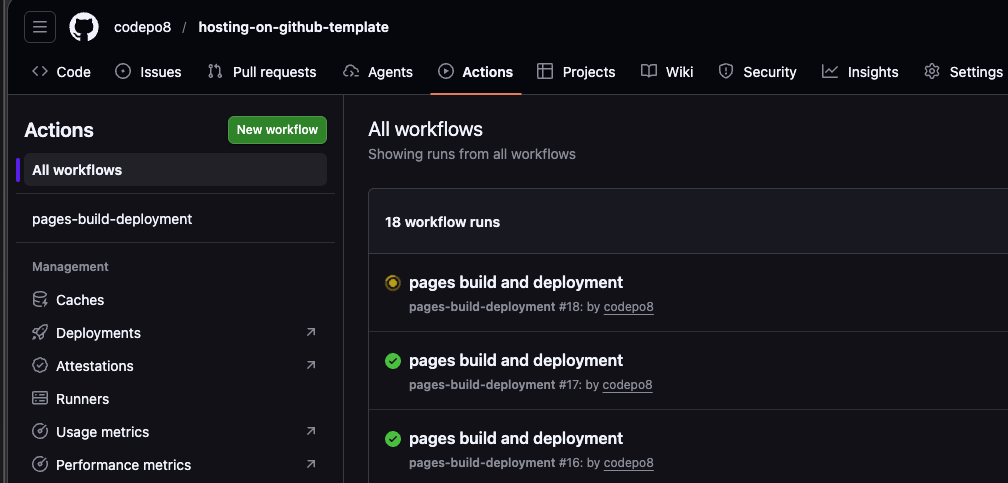

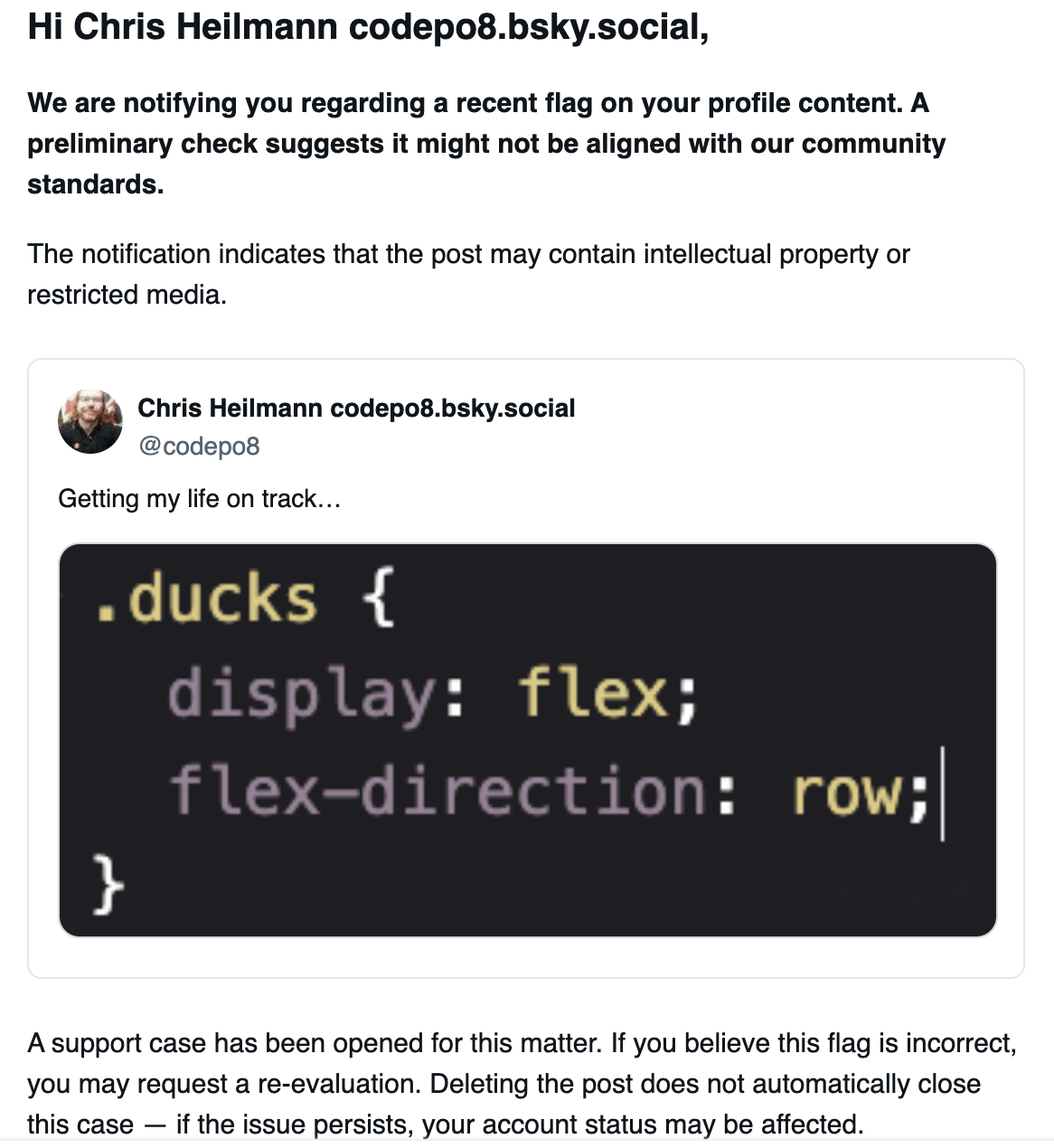

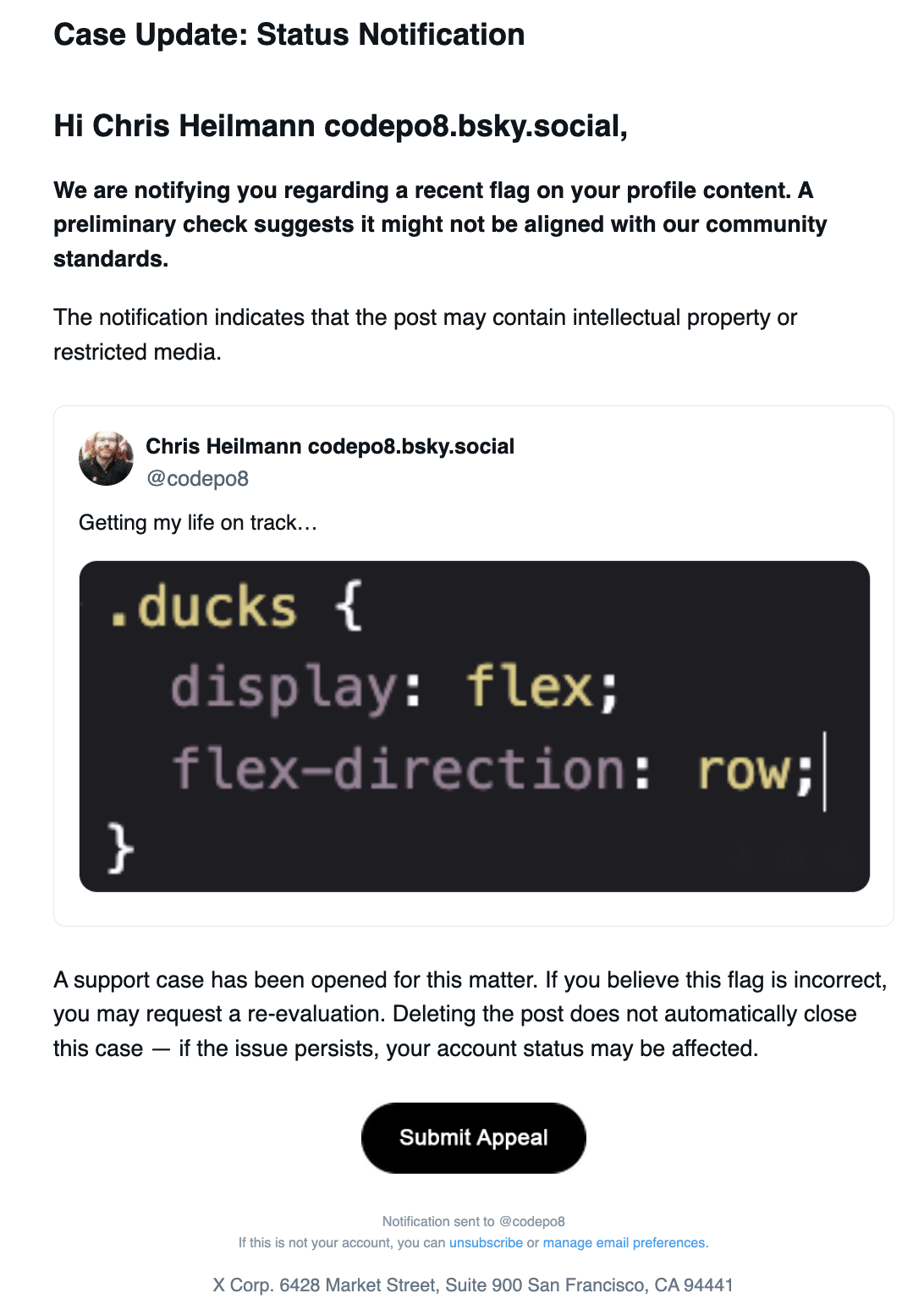

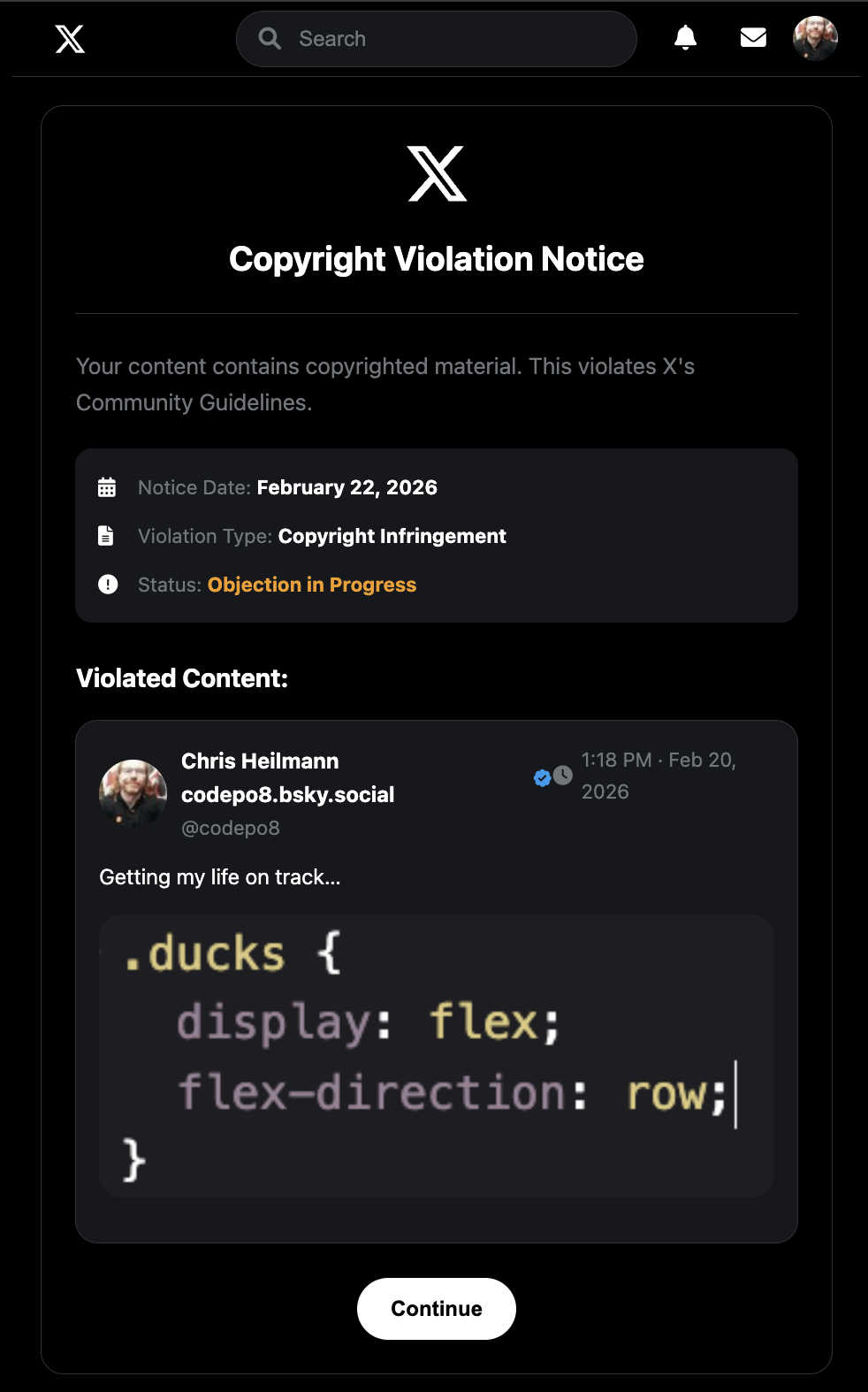

The mail looked like this:

The content was the following:

Case Update: Status Notification

Hi Chris Heilmann codepo8.bsky.social,

We are notifying you regarding a recent flag on your profile content. A preliminary check suggests it might not be aligned with our community standards.

The notification indicates that the post may contain intellectual property or restricted media.

Chris Heilmann codepo8.bsky.social

@codepo8

Getting my life on track…

Tweet Media

A support case has been opened for this matter. If you believe this flag is incorrect, you may request a re-evaluation. Deleting the post does not automatically close this case — if the issue persists, your account status may be affected.

Submit appeal

Notification sent to @codepo8

If this is not your account, you can unsubscribe or manage email preferences.

X Corp. 6428 Market Street, Suite 900 San Francisco, CA 94441

I had opened the mail on my second monitor as I was still wrapping up work on the main one and thought immediately that this is silly, why would they flag this tweet as a copyright issue? I even took a screenshot as I wanted to complain about this nonsense on other social media platforms. But I also wanted this issue to be resolved quickly, so I clicked the “Submit appeal” button.

What I should have done instead:

- Verify that this is really a legit mail by checking the sender and the URL of the link.

Third Mistake: not checking the URL of the link or the sender of the mail.

In my rush and glancing on the second monitor I only saw the “Submit appeal” button and clicked it. I didn’t check the URL of the link, which was not an X domain, but `https://cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/velitoya.com/codepo8`. I also didn’t check the sender of the mail, which was not an X email address, but `X Notices `. It is interesting to see that they use a secondary obfuscation by going through AMP…

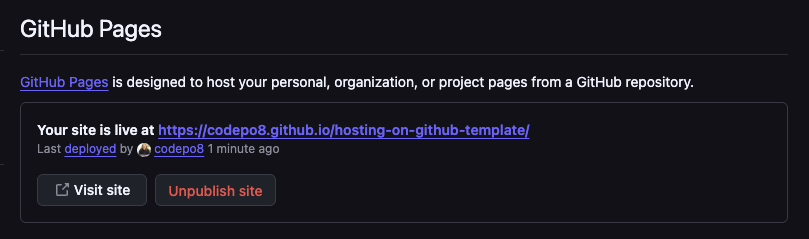

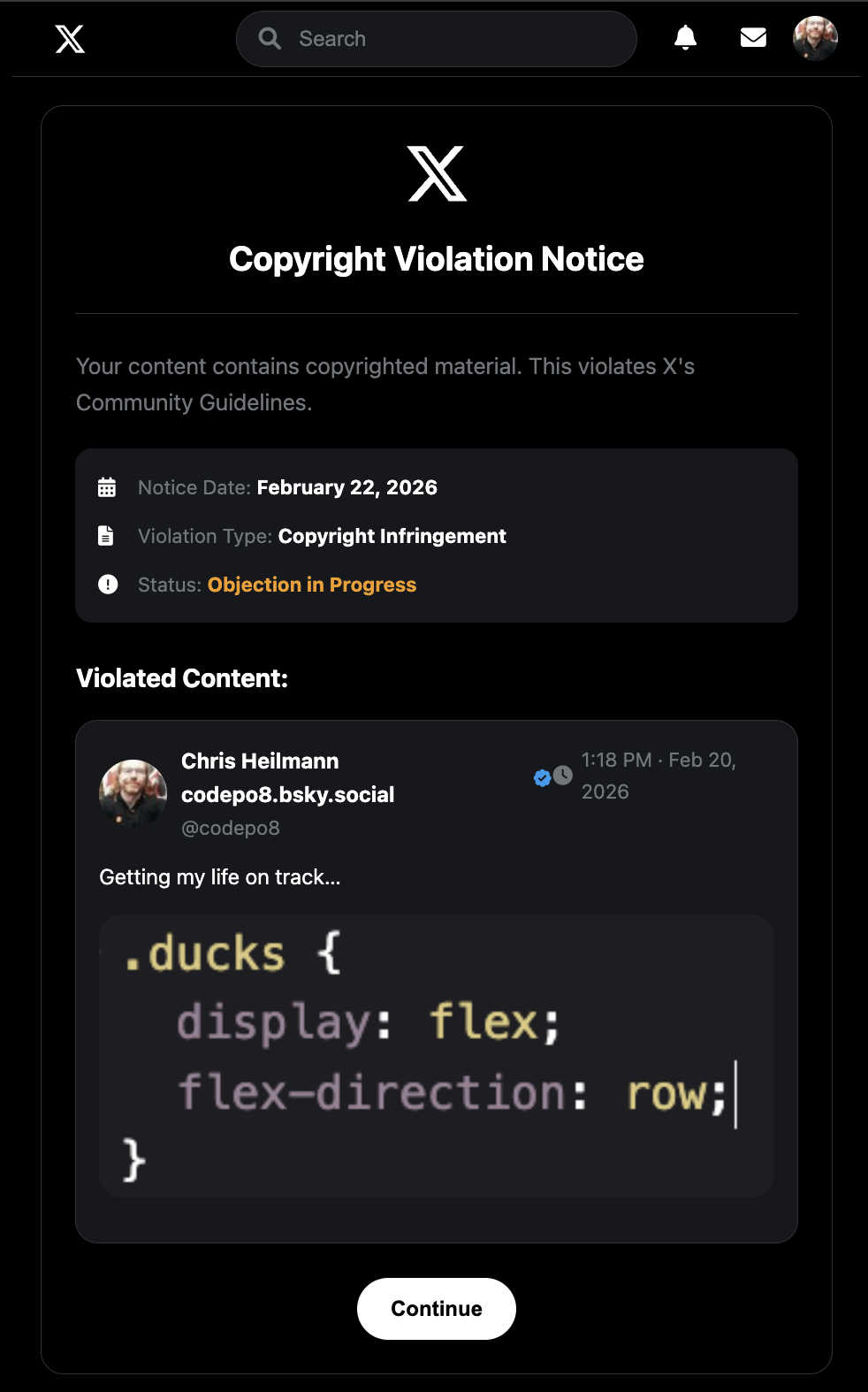

The interface it showed me looked pretty legit and redirected to `https://noticedirect-x.com/copyright/codepo8`.

The text on the page was the following:

Copyright Violation Notice

Your content contains copyrighted material. This violates X’s Community Guidelines.

Notice Date: February 22, 2026

Violation Type: Copyright Infringement

Status: Objection in Progress

Violated Content:

Chris Heilmann codepo8.bsky.social

@codepo8

1:18 PM · Feb 20, 2026

Getting my life on track…

Tweet Image

Continue

I thought this looked pretty legit, so I clicked the “Continue” button and it took me to a page that asked for my X login details.

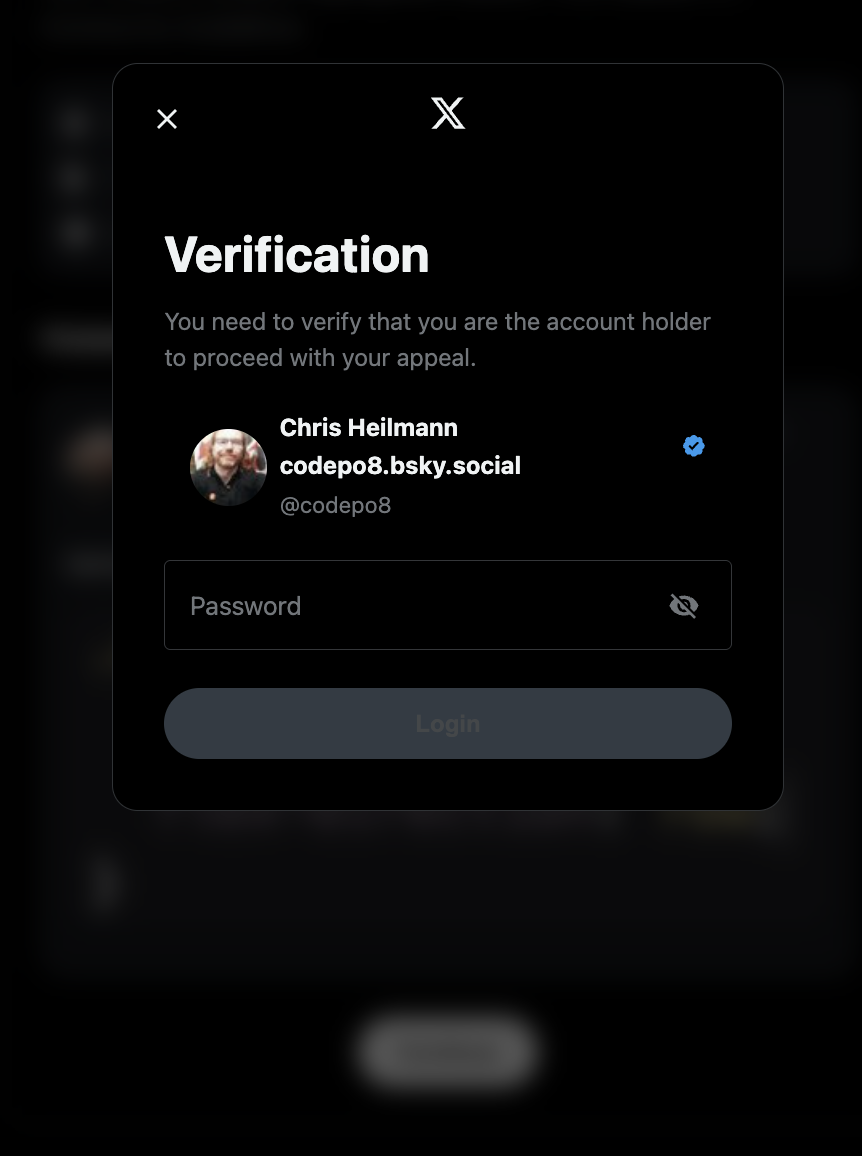

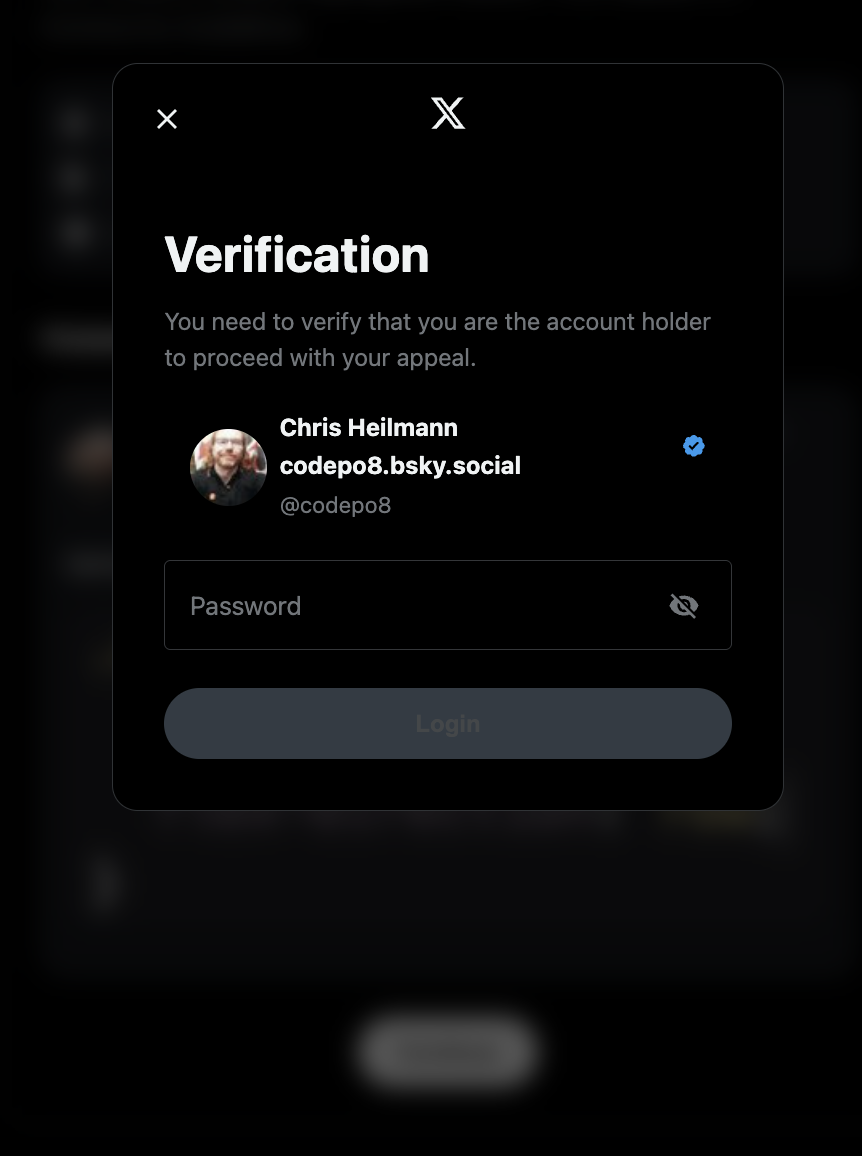

Verification

You need to verify that you are the account holder to proceed with your appeal.

Chris Heilmann

codepo8.bsky.social

@codepo8

Password

Login

Notice that It showed my account with the correct image and all details. Well done, you bastards.

Fourth Mistake: not realising a fake form despite using autofill.

I store my passwords in my browser and I use the autofill function to log in to sites. So when I got to the login page, it should have triggered the autofill feature, but it didn’t. I should have realised that this is a sign that this is not a legit login page. Instead, I thought maybe the phishing site is just not well made and doesn’t trigger the autofill, so I entered my login details manually.

What I should have done instead:

- I should have realised that the lack of autofill is a sign that this is not a form hosted on the correct domain.

Fifth Mistake: allowing myself to be kept busy while the phishing attack is happening.

After I entered my login details, I was taken to a page that said that my appeal is processed and – get this – it asked for me to verify my identity further by asking for a scan of my passport, credit card and other personal details. This is where I was out and knew that I had been phished. Luckily for me, as a different person might have been tempted to enter these details, losing even more control over their account and personal information.

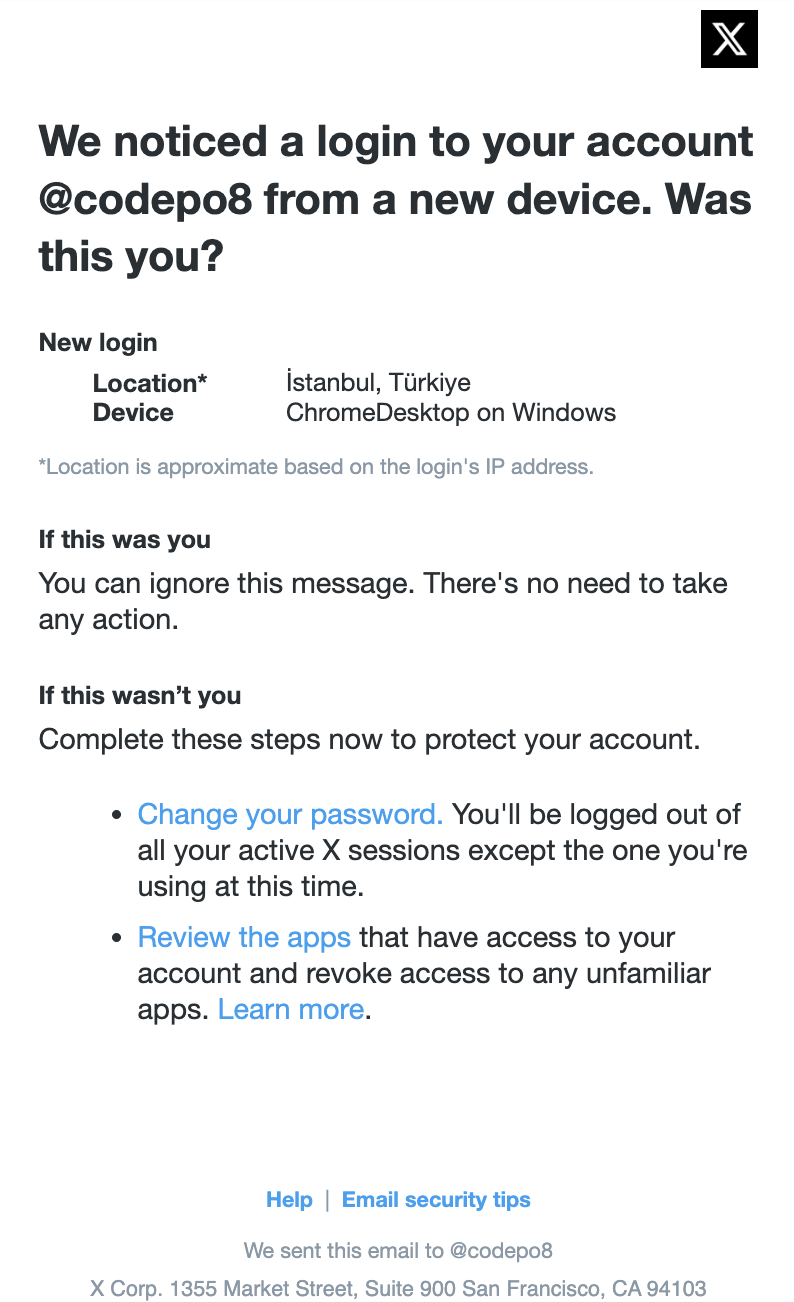

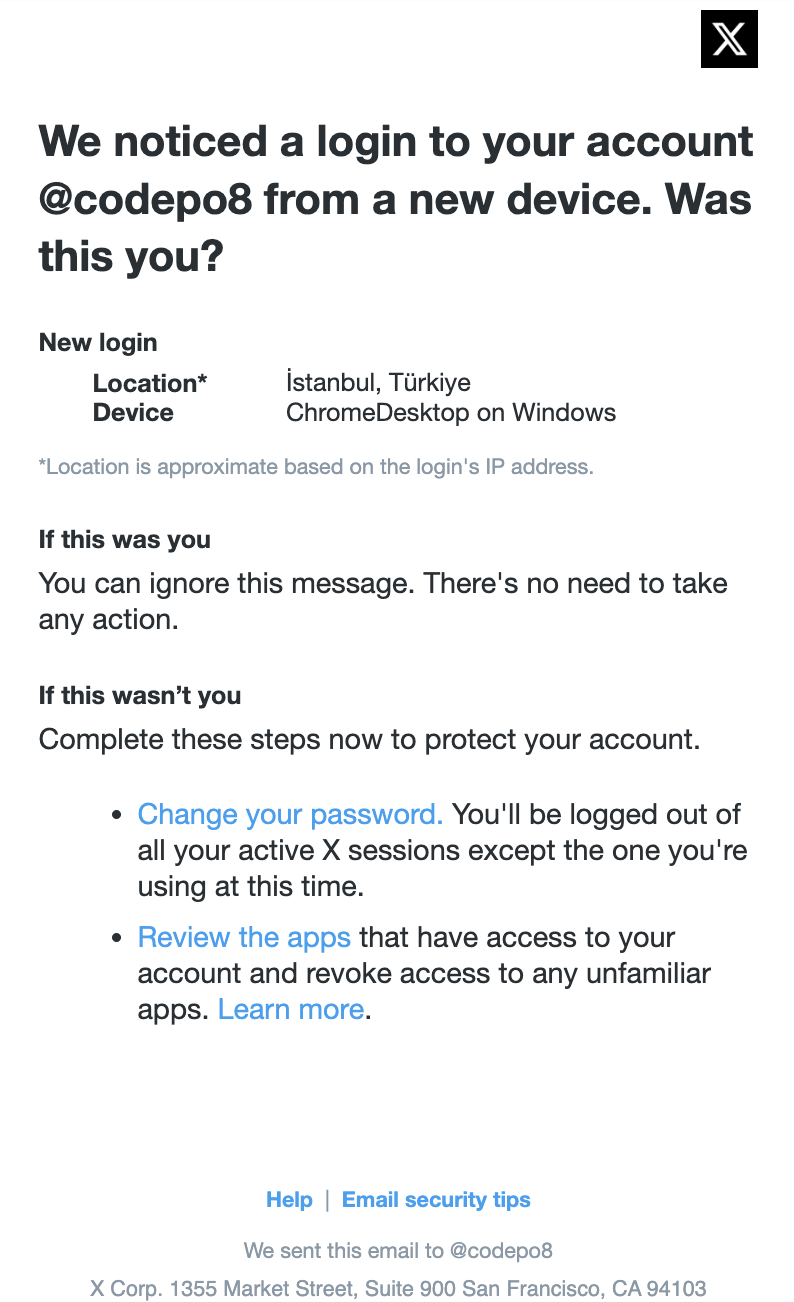

In the meantime, I got a notification on my phone that there was a login attempt from an unrecognized device:

New login

Location*İstanbul, Türkiye

DeviceChromeDesktop on Windows

*Location is approximate based on the login’s IP address.

I immediately went to my X account and try to my password, but the damage was already done. Instead of being able to change my password, I got a message that my account is locked and I need to use my authentication app to unlock it. I don’t have an authentication app set up for my X account, so I was locked out of my account and had to go through the account recovery process.

Meanwhile, a second email came in from X that stated that the email of my accoungt has been changed to `ashleyhavilii@gmail.com`.

Your email address has been changed

The email address on your account codepo8 has been changed to ashleyhaviliigmail.com. Based on this change, please be aware that additional changes to your account may be restricted temporarily.

If you did not make this change, please secure your account.

Any attempt to access the account ended in a message that the account is locked and I need to use my authentication app to unlock it. I filed a complaint with X support.

What I should have done instead:

- I should have immediately tried to change my password and enable two-factor authentication on my account

- Use an authentication app to secure my account instead of SMS-based two-factor authentication, which is less secure and X doesn’t even support it anymore.

Where I am now…

So, this is where I am now. I have lost access to my X account and I am going through the account recovery process. I have also contacted X support to try to get my account back. The first attempt was not successful and currently I should wait seven days before I can try again. Seven days in which the attackers have full control over my account and can do whatever they want with it. I understand that I made a stupid mistake entering my login details on a phishing site, but I hope that X support will be able to help me recover my account. After all, I am a long-time user of twitter and I have been using it for 20 years, so I hope that they will be able to help me recover my account which had the same email since 2006 and a backup phone number that I have access to.

The biggest issue is that I have a lot of followers on X and I use it for my work, so losing access to my account is a big deal for me. I also have a lot of personal memories on my account, so I really hope that I will be able to get it back. I have used X as “write only” for long time – I post there, but I don’t really interact with other users, which is also why I didn’t care enough for it to keep all the security measures up to date. I didn’t have an authentication app set up, which is another mistake. I thought that SMS-based two-factor authentication would be enough, but I was wrong.

I will keep you updated on the situation and I hope that my experience can help others to avoid falling for phishing attacks and to secure their accounts better.

Conclusion

Here are the things I did you should not do:

1. Don’t do any security things in a rush.

2. Not question emails that look legit but seem very urgent.

3. Not check the URL of the link or the sender of the mail.

4. Not realising a fake form despite using autofill.

5. Not allowing yourself to be kept busy while the phishing attack is happening.

Stay safe out there and always double-check before you click on any links or enter your login details on any site. And if you do fall for a phishing attack, don’t panic, but immediately try to secure your account and contact support.